10 minute read

In this section we will examine some of the factors that analysts and portfolio managers look at when assessing potential investee companies. We will look at the regulation and guidance that applies specifically to companies in the financial services industry in Modules 2 and 3.

Corporate governance is the process by which a company is managed and overseen. Rules vary from country to country but at its core governance is about people, and process. Good corporate governance should lead strong business performance and long-term prosperity to the benefit of shareholders and the company’s other stakeholders (such as employees, consumers, and local communities) through the development of strong and appropriate cultures.

At its heart, corporate governance is about people (the individuals in the boardroom), in order to exercise their responsibilities effectively, those board members are supported by processes. These processes are of even greater importance in larger and more complex companies – in smaller companies management is more likely to have direct knowledge and access across the business, but this is harder in bigger businesses.

The effectiveness of the corporate governance of a firm often gives investors insight into the accountability mechanisms and decision-making processes that support critical decisions impacting the allocation of capital and long-term value prospects.

In practice, corporate governance comes down to two A’s: accountability and alignment.

Accountability

People need to be:

- Given authority and responsibility for decision-making; and

- held accountable for the consequences of their decisions and the effectiveness of the work they deliver.

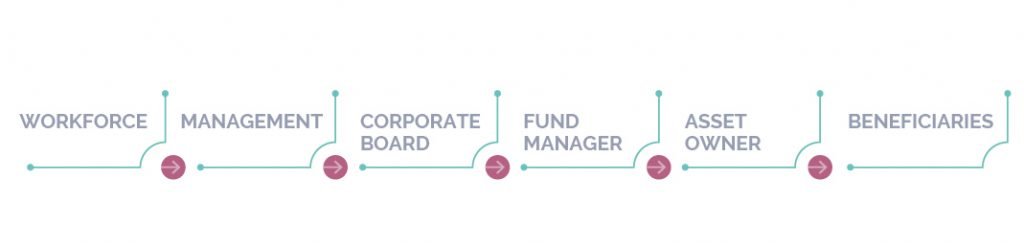

The below models help illustrate the flow of accountability through company structures and the investment chain.

Chain of accountability:

Circle of accountability:

Alignment – the agency problem

The agency problem has been identified as an inevitable consequence of the separation of ownership and control (management). The agency problem rises when the interests of the managers of a company do not align with the interests of the owners of the company, and the company may not be run in the way that the owners wish. This is especially likely to arise in situations where senior management has no ownership stake in the company they are employed to run.

Corporate governance attempts to ensure that there is greater alignment in the interests of management with the owners, through incentives as well as accountability.

Further Governance factors

There are several factors that relate to the governance of companies that can have an impact on their financial success. The Corporate Governance and Stewardship Codes of recent years have done a lot to address the more serious risk factors that contributed to company scandals such as Capron, PollyPeck, Enron and WorldCom (to name a few). However, risks and conflicts of interest can still arise from a range of factors, a few of the key factors and areas of focus are summarised in this section.

1. Board composition

The wrong people, or not enough of the right people, in the boardroom are less likely to make the best decisions for the company, which could result in significant erosion of value.

There is strong academic evidence of the beneficial impact of diversity on boards on companies’ performance:

- A 2003 Forbes study found 1,000 firms to have a statistically significant positive relationship between the presence of women or minorities on boards and the firm value (measured by Tobin’s Q – a valuation measure based on the ratio between a company’s market value and the replacement cost of its assets).1

- A further study in 2017 concluded that diversity of directors on a board reduces stock return volatility and that firms with diverse boards tend to adopt more stable and persistent policies, as well as tending to invest more in research and development. The study found that greater diversity on boards on average led to higher profitability and firm valuations.2

2. Disclosure and reporting

One of the key challenges that investors face when assessing the ESG credentials of a potential investor is the lack of consistent and robust data. This is because reporting requirements and expectations around ESG data vary hugely across sectors and markets.

Companies may attempt to mask weak performance within their reporting, sometimes through the use of alternative performance metrics (APMs). These are measures that are adjusted forms of the accounting standard approved measure of performance, often referred to as ‘adjusted’ or ‘underlaying’. Their use sometimes indicates that management is keen to flatter performance as the elements omitted through the adjustments may be hard to justify objectively. Both the European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA) and the International Accounting Standards Board (IASB) have issued guidance on the use of APMs which allows their use so long as they are not shown more prominently than, and are accompanied by the official measures.

3. Auditing of accounts and financial reports

Auditing is intended to provide an independent assessment of the financial reports of a company, to provide some assurance that the reports accurately reflect the position and performance of the business in question.

The independence of audit firms is a potential weakness or conflict of interest as many large audit firms also offer non-audit work such as consulting work and tax advice to the same companies that they audit. Regulation in the EU has removed some of the most obvious conflicts of interest by defining the non-audit services that a firm may provide to an audit client, as well as placing a monetary limit on their overall value.

Behavioural independence, or rather the lack thereof, can also pose a risk. Natural human tendencies to seek consensus run counter to the role of an auditor, requiring auditor teams to intentionally maintain skepticism through the process. Audit firms also tend to serve their clients for surprisingly long periods of time (Deloitte and its predecessor have been auditing Proctor & Gamble in the USA since 1980), which can further reduce independence. Many markets, however, including the EU, now impose a limit on auditor tenure (20 years).

The nature of the auditing process also leaves room for potential frauds to slip through the net. Auditing is a sampling process that does not examine every element, and the depth of sampling undertake is highly dependent on the auditor’s assessment of the quality of the company’s own systems and financial controls.

4. Executive pay

Executive pay can be problematic for several reasons. Concerns about fairness and income and wealth disparity often center on the extent to which executive pay exceeds the experiences of other employees. Pay ratios, which compare the remuneration of the CEO with the firm’s average worker, demonstrates and can reveal sizeable differences between executive teams and everyone else, often hundreds to one.

As many executives pay packages also include a performance linked bonus, there can often be disagreement between shareholders and management regarding what constitutes good performance and therefore the appropriate size of bonuses. Investors tend to judge corporate performance based on the strength of a company’s share price, whereas companies tend to consider performance within the business itself, which may not be reflected in the share price as a function of market sentiment rather than business performance.

5. Shareholder rights

Exploitation of minority shareholders could involve money being siphoned out of the business in ways that benefit the controlling shareholders but not the wider shareholder base.

In most countries, minority shareholders are protected within corporate governance codes or by law from being exploited by dominant or controlling shareholders through measures such as minority shareholder voting rights on significant transactions.

Pre-emption rights ensure that shareholders have the ability to maintain their position in a company by having the opportunity to buy an equivalent number of shares in a new issue to maintain their position. This is fundamental to many, but not all, market company laws. The US for example does not enforce this practice.

Dual class shares can be disadvantagous to minority or later stage investors where one of the classes is restricted to founders, or early-stage investors who receive multiple votes compared to the class of shares that are available to subsequent investors. Dual class shares are uncommon outside the US, where they are more common amongst startups and provide some stability and incentive in the early life of a company.

6. Business ethics and culture

A company needs to abide by the laws of its home country (its country of incorporation) and any laws of countries in which it operates. Whilst many companies believe that obedience to the laws is sufficient, investors are increasingly expecting more than this, expecting companies to be conscious of business ethics and broader responsibilities to stakeholders and communities.

Read: Pages 1-7 ‘How to Design an Ethical Organization’, Harvard Business Review

Read: Pages 1-7 ‘How to Design an Ethical Organization’, Harvard Business Review

Key points:

- Unethical behavior can have a significant toll on a business by damaging reputations, harming employee morale, increasing regulation costs and exposing a company to substantial fines

- Well-meaning people can be more ethically malleable than you might expect – context plays a surprisingly dominant role in how individuals assess and react to a situation

- The authors identify four critical features that need to be addressed when designing an ethical culture:

- Explicit values – employees should be able to easily see how ethical principles influence a company’s practices. Mission statements need to be more than just words on paper. They must undergird strategy and policies around hiring and firing, promoting and operations so that core ethical principles are deeply embedded throughout the organisation.

- Thoughts during judgement – behaviour tends to be guided by what comes to mind immediately before engaging in an activity, so keeping ethics top of mind can have a strong influence on behaviour.

- Incentives – along with income, employees care about doing meaningful work, making a positive impact, and being respected or appreciated for their efforts. Ethical cultures provide explicit opportunities to benefit others and reward people who do so with recognition, praise and validation.

- Cultural norms – ‘descriptive norms’, how people (peers) actually behave tend to exert a higher level of social influence that good leadership/ examples from the top. Although the natural tendency is to focus on cautionary tales or ‘ethical black holes’, doing so can make undesirable actions seem more common than they really are and potentially increase the rate of unethical behavior. Focusing instead on ‘ethical beacons’, those who behave in an exemplary fashion, can have the opposite effect.

7. Supply chains

In the modern era of connectivity and technology proliferation, environmental, social or governance risks buried in a company’s supply chains are likely to be unearthed and exposed. This poses huge reputational and financial risks for companies. However, despite the risk most companies still do not assess or disclose against their full supply chain, opening themselves up to the potential unearthing of skeletons in their closets which they may not have been aware of.

This is a particular area of concern as human rights and labour violations in particular tend to occur deep within supply chains.

Module 2 goes into more detail on the current and upcoming regulation facing the financial services industry in Europe and North America.

1Carter, DA., Simkins, B.J. and Simpson, W.G. (2003).”Corporate governance, board diversity, and firm value. Financial Review, 38, pp. 33-53

2Bernile, G., Bhagwat, V. and Yonket, S. (2018). “Board diversity, firm risk, and corporate policies.” Journal of Financial Economics, 127 (3), pp. 558-612