12 minute read

It is clear retail investors perceive that integrating sustainability into their lives starts with actions perceived as smaller, easier to control and closer to home.1 Many investors look to their wealth manager or financial adviser for guidance across all the financial decisions, not just investments. With this role comes a responsibility to promote behaviours and actions that promote a more sustainable lifestyle.

![]() Read: Katherine White, Rishad Habib, David Hardisty – How to SHIFT behaviours to be more sustainable pg 21, 24 (from beginning of new section) -31 (end of 3rd paragraph)

Read: Katherine White, Rishad Habib, David Hardisty – How to SHIFT behaviours to be more sustainable pg 21, 24 (from beginning of new section) -31 (end of 3rd paragraph)

Key points:

- The SHIFT framework proposes that consumers are more inclined to engage in pro-environmental behaviours when the message leverages psychological factors:

- Social influence

- Consumers are often effected by the presence, behaviours, and expectations of others

- Social norms – beliefs about what is socially appropriate and approved can influence behaviour e.g. not littering.

- The Theory of Planned Behaviour suggests attitudes and perceived behavioural control shape intentions and predict behaviour

- Descriptive norms refer to information on what other people are doing and can be a powerful source of influence

- Injunctive norms convey what behaviours other people approve and disapprove of

- Highlighting and demonstrating either descriptive or injunctive norms can be a tool to motivate desired behaviour

- Social identities – sense of identity stemming from group membership. People are more likely to take an action if other members of their group/desired group are also doing so

- Highlighting a shared ingroup identity can increase reciprocity to certain information

- Social desirability –people tend to make sustainable decisions to make a good impression on others

- People are more likely to act in a socially desirable way in public when others can see/judge them

- Making public commitment to actions makes people/organisations more likely to follow through on them

- Habit formation

- Making sustainable action easy can encourage new, better habits; As can penalising adherence to old unsustainable habits (eg fines and taxes)

- The habit discontinuity hypothesis suggests that if the context in which habits arise changes in some way, it becomes difficult to carry out the usual habit

- Implementation intentions – considering the steps to forming new behaviour can be an effective motivator

- Sustainable action can often be seen as hard, time consuming, or expensive. Making sustainable options the default can make them an easier choice

- Prompts can be used before behaviours occur to remind people to make sustainable choices

- One off sustainable action can be easily encouraged through incentive but this works less well/ has more potential to falter for long-term actions

- Feedback – specific information on performance regarding a task or behaviour can encourage people to compete with their own past performance, or with others

- Individual self

- The self-concept – consumption is a way for individuals to maintain positive views of themselves (their self-view). This is the same driver than prompts people to often seek out information / opinions that support what they already believe.

- Self- consistency – people want to view themselves as consistent, as well as positive – therefore one positive/ sustainability related action is likely to beget another, especially if commitment is made publicly or in writing, but conversely the first action can be hard to achieve.

- Self-interest – highlighting the benefits to self of certain behaviours, products or services is a powerful motivator, especially if they counteract the (perceived or real) barriers to sustainable action.

- Self-efficacy – refers to an individual’s belief that they can do something and that it will have the desired outcome /9a form of confidence or self-belief). Individuals are more likely to behave sustainability if their self-efficacy is high.

- Individual differences – personal norms or beliefs in ones personal obligations are linked to an individual’s self-standards and can have an impact on propensity for sustainable behaviour.

- Demographics have been shown to play a big role in sustainable behaviour/ consumption – studies have observed women tend to make more sustainable decision along with younger and more highly educated demographics

- Feelings and cognition

- Consumers tend to take one of two routes – one is driven by affect and cone by cognition.

- Fear, guilt and sadness at an individual and a collective level can be drivers of sustainable behaviour

- Individuals are more likely to engage in any behaviour when it makes them feel good/ less bad or gives them pride. Positive emotions towards the environment for example are likely to prompt environmentally friendly actions.

- Information, learning and knowledge – can be a barrio to uptake in sustainable behaviour and a means to prompt more

- Eco-labelling is a means of conveying information about a product or service and can help people to make more informed, better decisions.

- Framing – messages can be framed to encourage certain choices. for example, most consumers care more about future losses than future gains so messages about mitigating future losses and more effective than describing future gains

- Tangibility

- A challenge to sustainable consumption and behaviour is that actions and outcomes can seem abstract, vague and distant.

- Matching temporal focus – sustainability is naturally future-focused, whereas consumers are more often present-focused. Individuals with a greater focus on the long-term/ future goals tend to make more sustainable decisions.

- Communicate local and proximal impacts – focusing on immediate/ close to home behaviours and impacts can make sustainable actions and outcomes more tangible and relevant.

- Concreate communications – communicating the immediate impacts of sustainability challenges and outlining clear steps to make a difference make them more tangible.

- Encourage the desire for intangibles – promoting dematerialisation and a decreased focus on material consumption and possessions is crucial in broader societal shifts to more sustainable behaviour and is synonymous with a longer-term/ future-focused view which engenders more sustainable behaviour

- Social influence

Being an agent of change

Read: The Embedding Project – Becoming an Agent of Change pg 4-17

Read: The Embedding Project – Becoming an Agent of Change pg 4-17

Key points:

- Privileged insiders are those of us who have reaped advantages associated with our education, our socio-economic background, our citizenship, our gender, or our race. Privileged insiders hold great transformational potential, within organizations as well as at governmental or system level.

- Decisions at pivotal moments in your career can shape whether and how you engage in the work of change.

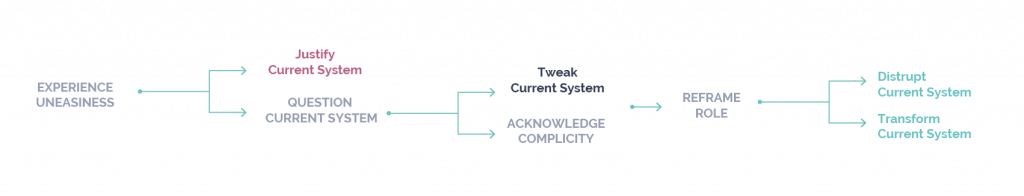

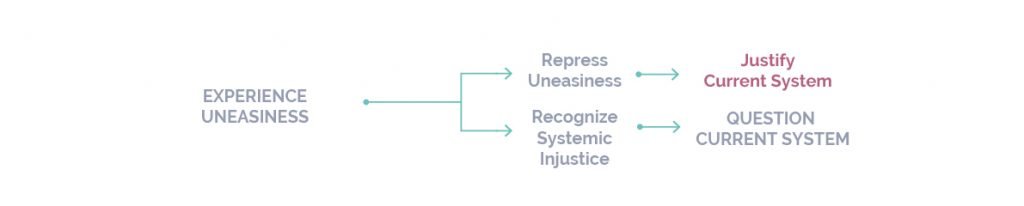

- Many people first experience a growing sense of uneasiness when they notice a contradiction between their personal situation and the suffering of others or the degradation of the natural environment.

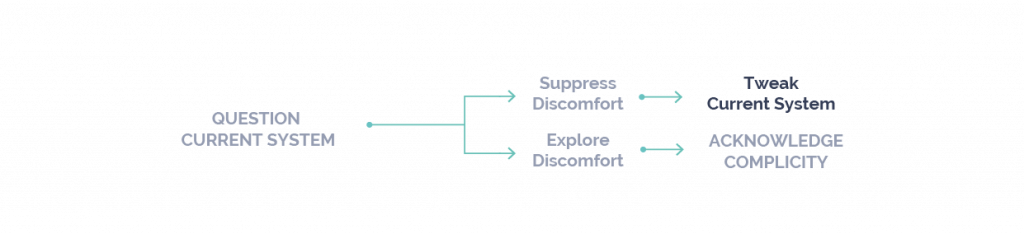

- What one decides to do with this feeling of uneasiness is crucial:

- Those who explored this uneasiness often uncovered patterns of injustice in society. Questioning aspects of the socio-economic system can lead to a shift in ones understanding of the world.

- How individuals react to this experience shapes the type of agent of change they can become:

- Those who repress their discomfort in the system tend to focus their efforts on working within the current system. Those who focus on tweaking the system can enable small improvements but are unlikely to address the fundamental underlying issues.

- Those who are willing to make the difficult step to question their own assumptions and role in perpetrating the existing system of which they are the beneficiaries then often find that they are motivated to take action as a way to work through what is often quite a personal crisis

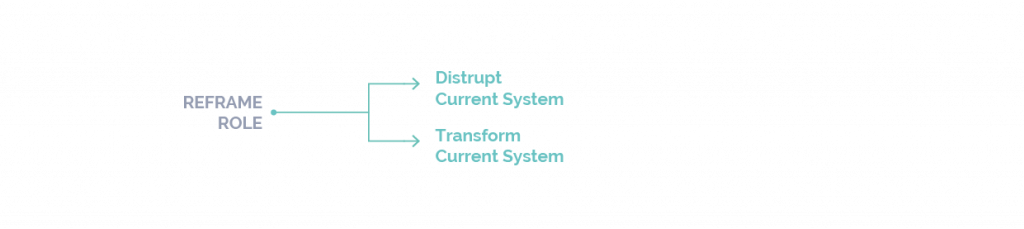

- The key to moving forward is for you to identify how you can use your privilege – this could be your skills, resources, networks, or your influence.

- The next step for many was then to either leverage their role or fundamentally transform it to disrupt the current system.

Exercise: Reflecting on Your Own Journey – The Embedding Project – Becoming an Agent of Change pg 18 -19

Exercise: Reflecting on Your Own Journey – The Embedding Project – Becoming an Agent of Change pg 18 -19

Read: Being an effective agent of change pg 4 – 14

Read: Being an effective agent of change pg 4 – 14

Key points:

- Preparing yourself to be an effective sustainability change agent requires:

- Demonstrating that you know the business.

- Establishing a track record of making good decisions on behalf of the business.

- Connecting your ideas to the business strategy, not the other way around.

- Knowing when to bring ideas forward, and when to wait – Identifying ‘transition stages’ or time periods where change is more likely to take off requires patience.

- Breaking the bigger vision down into manageable chunks that can be more readily adopted by the business. Small changes that require minimal effort are more easily adopted and lay the ground for larger change.

- Consistently demonstrating a commitment to the business.

- Challenging the CEO respectfully, and being willing to be challenged yourself.

- Harnessing your passion, whilst keeping your emotions in check to avoid eroding credibility.

- Keeping sustainability from being perceived as a pet project. In order to be effective, sustainability needs to be integrated across a business and not just seen as the territory of one individual or team.

Addressing the issues/ Changing the system

Read: Rewiring the Economy. Ten tasks, ten years pg 3, 5- 17

Read: Rewiring the Economy. Ten tasks, ten years pg 3, 5- 17

Key points:

- Rewiring the Economy is CISL’s ten-year plan to lay the foundations for a sustainable economy. It is built on ten interconnected tasks, delivered by leaders across business, government and finance.

- The ‘Great Acceleration’ that began in the 1950s remains at full pace. (The Great Acceleration refers to the dramatic acceleration in human enterprise and the impacts on the Earth system over the last two centuries.2)

- A new quality of dialogue is needed between business, government and finance – Governments have cited the central role of business in delivering the SDGs, but should not assume this will happen without necessary incentives and ground rules.

- Today, the success of economies is generally measured in terms of growth rather than positive outcomes for people, such as those embodied in the SDGs – There seems to be a strategic chasm between where the world agrees it should be headed (the SDGs) and the direction of the economy.

- CISL condense the SDGs into six broad social and environmental ambitions:

- Basic needs – food, water, energy, shelter, sanitation, communications, transport, credit and health

- Wellbeing – enhanced health, education, justice and equality of opportunity

- Decent work – secure, socially inclusive jobs and working conditions

- Climate stability – limit GHG levels to stabilize global temperature rise below 2C warming

- Resource security – preserve stocks of natural resources through efficient and circular use

- Healthy ecosystems – maintain ecologically sound landscapes and seas for nature and people

- The CISL ten-year plan focuses on creating the enabling conditions for sustainable business to encourage capital to flow into sustainable business models.

- The economy is dependent on inputs of labour, natural resources and ecosystems to function, in turn producing goods and services, wealth, waste and emissions as outputs. Some of these inflows and outflows are accounted for financially, while others – like clean air, pollination and rainfall – sit outside public or private balance sheets and are, effectively, free. If the draw down on these resources (the ‘global commons’) is not managed carefully, then economic and social progress is hampered.

- Ten tasks for economic leaders:

Government – Governments set the rules of an economy, steering its development. They provide the signals and conditions necessary to adjust economic behaviour through government policy, regulation, spending and public service practice.

- Measure the right things, set the right targets – Governments can set targets for social and environmental progress, and adopt new measures to track how well the economy is delivering them.

- Align incentives to support better outcomes – Governments can use regulation and fiscal policy to pursue environmental and social goals, and support sustainable business models.

- Drive socially-useful innovation – Governments can create drivers and incentives for innovation aligned with core sustainability goals, and can exemplify and enable sustainable business.

Finance – If governments steer the economy then finance provides its fuel. As a universal influence on business, the role of finance in rewiring an economy is simple: to steer capital towards economic activities that support the future we want, and away from activities that do not.

- Ensure capital acts for the long-term – Investors of capital can demand more from their money, using their influence to drive long-term, socially useful value creation in the economy in the interests of their beneficiaries.

- Price capital according to the true costs of business activities – Capital providers, and those who regulate them, can jointly consider how to reflect social and environmental risk factors in the cost of capital.

- Innovate financial structures to better serve sustainable business – Financial intermediaries in particular can apply their influence and creativity to direct capital into business models that serve society’s interests.

Business – If finance is the fuel of an economy, then business is its engine. Any serious rewiring of an economy will therefore require active business engagement and leadership.

- Align organisational purpose, strategy and business models – Within a commercial context businesses can explicitly set out to improve people’s lives whilst operating within the natural boundaries set by the planet.

- Set evidence-based targets, measure and be transparent – Businesses can contribute to a sustainable future by setting evidence-based targets, measuring the right things, and reporting progress.

- Embed sustainability in practices and decisions – Businesses can embed new ways of thinking in their operational practices and decision making.

- Engage, collaborate and advocate change – Businesses can use their influence to engage communities, and build public and government appetite for sustainable business.

Long-termism

One of the key components on successful sustainability leadership is, as has been alluded to in a lot of the materials in this module, to reframe your mindset as a leader away from thinking in terms of short-term success towards thinking beyond your tenure at your organisation. The tendency to think in short-term horizons is often directly correlated to the notion of shareholder capitalism, as shareholders definition of success from an economic perspective tend to be counted in shorter time periods, which can lead to neglecting other longer-term activities.

Read: Michael Useem ,Dennis Carey, Brian Dumaine and Rodney Zemmel (Wharton Business School) – Long-term thinking is your best short-term strategy

Read: Michael Useem ,Dennis Carey, Brian Dumaine and Rodney Zemmel (Wharton Business School) – Long-term thinking is your best short-term strategy

Key points:

- Long-term strategies create solid growth, more jobs and ultimately better rewards for shareholders

- Four broad, basic principles can be applied by CEOs and leadership teams implementing long-term strategies:

- Create a purpose that is greater than profit – motivate employees by helping them feel that their jobs have meaning and that they are part of something bigger.

- Translate that purpose into a long-term business strategy and then get strong buy-in from your board and investors.

- Formulate metrics beyond EPS (earning per share) and near-term financial performance that help directors and investors understand whether the business is making progress on its long-term goals.

- Foster a culture that always focuses on long-term, profitable growth to make sure your long-term strategy is well executed.

Case study of an agent of change/ sustainability leader – Paul Polman former CEO of Unilever.

Watch: 0:55 – 22:30 Harvard Business School interview video with Paul Polman

Watch: 0:55 – 22:30 Harvard Business School interview video with Paul Polman

Key points:

- What leaders do is more important than what they say.

- Since Milton Friedmann’s concept of shareholder primacy took over how we think, businesses have become more short-term in their thinking and less concerned with how they behave as part of the societies in which they operate.

- Companies that become too short-term in their mindset suffer by underinvesting in people, factories and brand support.

- In order to facilitate a change and a return to the earlier values of Unilever, taking measures such as stopping quarterly reporting gave the company the pace it needed to think in a more long-term manner.

- Private business needs to be involved to address the societal issues summarised by the SDGS, both because governments do not have the funding, capacity or innovation resources to tackle them alone, and because business plays such a role in global systems.

- Large global corporations, like Unilever, have a great deal of liberty, but also responsibility, given the scale of their customer base. Scale can be leveraged to drive transformative change.

- Being driven by a stronger sense of purpose and a bigger picture, and also feeling a bit uncomfortable about it, are key elements to developing an agenda for change.

- The role of a CEO in a company like Unilever is to ensure that the system works.

- A business that is run on principles and purpose, rather than rules, laws or regulations will flourish and nurture innovation.

- To be a good leader you must know yourself – what motivates you.

Unilever is an interesting example of a company that is both, by most definitions, a sustainability leader (encapsulated in the work of the Unilever Sustainable Living Plan) but also continues to be one of the world’s biggest plastic polluters.3 They face an ongoing struggle between facilitating access to health and hygiene products in low income developing countries, through tools such as single portion soaps, and the plastic waste that such initiatives produce. This dilemma highlights the need for careful consideration of the social impacts of sustainability initiatives and the transition to a carbon neutral low waste economy.

1 White Marble Consulting research, unpublished

2Futureearth.org. n.d. [online] Available at: <https://futureearth.org/2015/01/16/the-great-acceleration/>.

3Eonnet, E., n.d. The Coca-Cola Company, PepsiCo and Nestlé named top plastic polluters for the third year in a row | Break Free From Plastic. [online] Break Free From Plastic. Available at: <https://www.breakfreefromplastic.org/2020/12/02/top-plastic-polluters-of-2020/>.